Frequently Asked Questions

- Matthew Moss - The Man and the Artist

- What are Original Paintings?

- Original Transparencies

- Art Rental Service

- Fine-Art Books

Fine-Art Books

Caring for Old Masters Paintings

A Simple Method to Safeguard Your Paintings

Tells you:

- How to choose a safe environment for your painting.

- Hanging your painting in a way that avoids potential damage.

- Maintaining and caring for your painting to save on expensive professional restoration services.

You Learn from Practical Examples:

- How to take care of your paintings

- Prolong and extend the life of your painting

- How to avoid deterioration to your painting

- You learn how to look after paintings on canvas, timber and copper

- You learn the history of oil paintings from the twelfth century to the present as well as tempera paintings and icons

Chapter Headings Include:

Materials artists have used from pre-historic times through the Renaissance. Practical examples on how to examine and handle old paintings safely. What is the safest environment to hang your painting and what conditions will cause it to degenerate.

Watching out for, and avoiding, forgeries. Caring for Old Master Painting: their preservation and conservation, contains a practical guide, in the seven major European languages, to help you learn the terms most commonly used in conservation.

What professional artists and restorers have said about Caring for Old Master Paintings

- "I have enjoyed reading this most interesting and informative book, which taught me much that I didn't know before," John Unrau, Professor of Fine Arts, York University, Toronto.

- "I found Caring for Old Master paintings a very interesting guide to the whole world of fine Arts and Conservation. I found it easy to read and informative." Ian O.Morrison, national Museum of Scotland.

- "I read Caring for Old Master Paintings with great interest. I found it a very useful volume." M.Hadjidaki, Conservator of Works of Art, Athens.

- "I like the writing which is readable and clear and it is interesting to read examples and anecdotes which make quite a story." Debbie Duffin, Sculptor and author.

-

Because of his Italian training, the author is familiar with tools such as stereoradiography not commonly used by English-speaking conservators, as well as with a number of Italian conservation projects that make interesting reading. The discussion of means and philosophy is refreshingly objective and free from the emotional polemics of some recent publications in the field. Those working internationally will find the section listing conservation terminology in seven European languages very useful”.

Carol Christensen Conservation Department, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565

Extract from Caring for Old Master Paintings

Chapter 9: Conservation in the Twentieth Century

The period following the First World War saw a resurgence of interest in conservation. In France it went hand in hand with scientific research. Science could be used to study both the history and the technique of paintings

Dürer: the first artist to be x-rayed

Earlier research, such as that carried out by Sir Humphrey Davy and Chevreul, was in colours and pigments. The discovery of photography made available a new tool for the study of Old Master paintings. Some of the earliest photographic experiments of Niepce and Daguerre had been attempts in that direction. Photographers attempted, 1861, the first reconstruction of the Jan van Eyck Mystic Lamb . The triptych's wings were then in Brussels and Berlin while only the central panel remained in Ghent. The German physicist Rontgen who discovered X-radiation in 1895, quickly brought it into the service of the fine arts. His is the earliest known reference to the possible use of X-radiation in painting. In 1896 he discussed the absorption of the radiation by the lead white pigments contained in paintings. A year later, scientists X-rayed a painting by Albrecht Dürer and published a paper which proposed this method for the examination of works of art. From then onwards this type of research advanced in Germany and in France (under Ledoux-Lebart), and in Switzerland from the beginning of the First World War.

The end of the Second World War also prompted a revival of interest in the conservation of Old Master paintings. It stimulated interest in the research and development of new techniques and materials. This reawakening was a response to the damage which the war had inflicted on works of art through violence, theft, concealment and neglect. Later, natural disasters, such as the Florence floods of 1966 which destroyed Cimabue's 'Crucifix', gave an impetus to the study of new materials which could be employed in conservation. This developed a rapport between advanced scientific methods of analysis and new types of technology, both in the study of the nature of painting materials and their proper conservation.

How Nazi Germany stole van Eyck's 'The Mystic Lamb'

During the Second World War Government authorities hastily removed important paintings on timber, such as the Mystic Lamb by Jan van Eyck, from their normal environments. They often damaged them as a result. This was because of poor storage conditions and frequently shifting the paintings from location to location.

Germany itself lost a lot of art treasures because of bombing. In the early part of the war, the government decided not to remove art treasures to places of safety. They hoped, by this policy, to create a feeling of normality and security in their citizens. When heavy bombing began in earnest, many custodians of the nation's treasures risked their lives and sometimes died, removing artworks, libraries and paintings from the path of destruction. Governments shipped many of these treasures east, often to Poland from where they have never returned. American soldiers on arrival in Germany also plundered other works of art which reappear from time to time. In January 1991 the German Government paid $2.75m to the heirs of a Texas ex-serviceman to get back the remains of the medieval artworks, the Quedlinburg treasures. Trustees found the looted artworks in the soldier's estate after his death.

In May 1940 the authorities boxed the 'Mystic Lamb' and stored it for safety in the crypt of Ghent cathedral. Some weeks later they sent it to the Chateau de Pau in south west France close to the Spanish frontier. It began to show signs of deterioration en route, such as splitting and flaking of the paint layer. Restorers escorting the painting attempted first aid by securing the flaking areas with fine tissue paper and adhesive.

In August 1942 German authorities removed it from France to Germany itself where it remained until the Summer of 1944 in the castle of Neuschwanstein. There, conservators again treated the recurring paint blisters. As the war advanced in Germany, they removed the Mystic Lamb for safety to the salt mines of Alt Aussee. The authorities stored in a low ceilinged room partitioned with rough timbers known as the Mineral Kabinett. (34) During its sojourn in the salt mines which lasted until May 1945 the painting began to suffer further degradation. The German restorer Karl Sieber worked on the large panel representing the figure of St John, which had split along its length. Allowing for its peregrinations during the war, the painting was in stable condition when the American Third Army recovered it. The conditions of the salt-mines possibly helped, being a constant 7 C. temperature and 70% relative humidity. From there they shipped the painting to the central collecting point for the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives section of SHAEF (Supreme headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) in Munich. In August 1945 they sent it back, by air, to Brussels. After the painting's return to the Cathedral of Saint-Bavon in Ghent the authorities observed that the paint layer was still unstable and flaking, and the varnish layer degrading.

In 1950, Belgian decided to undertake a major conservation of the masterpiece. This aroused comment from prominent personalities in the Belgian academic world. They still had vivid memories of the London National Gallery cleaning controversy of 1947. So also were recollections of an earlier Dutch case involving Rembrandt's 'Night Watch'. They decided not to leave the decision of the methods and techniques to be adopted to the conservators and scientists who would carry out the operation. Instead, the Belgian government set up an international commission of art historians and members of ICOM (the International Council of Museums) to study the manner in which the conservation would be done. They were probably influenced by the principle that war (or here, conservation) is too serious to be left to the generals.

Van Eyck's technique revealed

They began a study of the history of the Mystic Lamb, with special reference to the materials used by the van Eyck. The commission also made a close examination of the physical condition of the painting. The purpose was, to determine the nature and the cause of the degradation, and to establish the pictorial aspects of the conservation they were about to commission. The research discovered that, apart from the restoration carried out in the Cinquecento (sixteenth-century), the artist himself had made alterations to the painting, including Adam's feet, while executing it. There were old repaintings along the back and around the head of the Lamb and the Lamb's ears, in the central panel. These came to light when the scholars examined the work under X-radiation analysis.

Bourdeau had restored the painting in 1818. Lorent worked on it in 1825 following a serious fire in the cathedral of Saint-Bavon in September 1822. The fire had damaged the masterpiece around the rear of the head of Christ. Donselaer also carried out restoration in 1858 and 1859. During the course of this restoration he repainted the blue mantle of the Virgin, previously damaged. He used Prussian blue and ultramarine, often in a tone different to that of the original and emphasized brown tints in some parts. Here he possibly did this with the intention of simulating age. Earlier studies (35) done on the van Eyck had also suggested that the painting was cut down in size at some time in the past.

The commission needed to consider those early repaintings concealing the artist's original colours and those repaintings which were contributing to the degradation of the masterpiece. The degradation of the varnish layer was causing some portions of the paint layer below it to flake off. There were also disharmonies evident in the total appearance of the painting. The lapis lazuli and the azurite of the sky which had come down to the present virtually unaltered contrasted noticeably with areas painted in copper resinates. These had darkened to a deep brown. To achieve a tonal balance the conservators' when they began working on the van Eyck, allowed ancient repaints to remain where they did not interfere with the original work. They also partially removed the ancient yellowed varnish layer.

A study of the pigments adopted by the artist revealed that he had built up the Virgin's robe with three layers of azurite bound in an oil medium. He had subsequently glazed this with lapis lazuli in a water soluble medium. The first layer had two sections of azurite in the form of a sandwich and this covered a section composed of azurite and lead white. Van Eyck had probably adopted this unusual technique as a low cost method of producing a medium blue tint. A study of the less critical sections of the painting by cross section analysis and by X-radiography showed that assistants had executed these portions.

Some of the degradation, noticed by Karl Sieber on the timber support in 1945, on the timber support, was still causing splitting and the separation of panels. Where the timber support was weakest, often in the softer sections of the timber, this continued to encourage paint losses. Professor Phillipot, the restorer responsible for the operation, treated them by impregnating the affected areas with a wax resin adhesive. He aided the operation using infra-red lamps set at 35-40 C. and applied the same treatment to the rear of the timber support. His intention here was to stabilize it in the uncertain ambiental conditions of the cathedral of Saint-Bavon. Here, without benefit of air conditioning, the temperature and relative humidity varied greatly depending on the season and the time of day. The international commission advanced ideas and suggestions which the conservators adopted during this restoration. These recommendations became the model and then the standard approach used in later museum conservation.

(34) The central region of Germany is rich in salt mines. These were planned as repositories for art works from the beginning of World War II. It was thought they would, unlike border zones, be less likely to became war risks. The region became part of the German Democratic Republic with the ending of the war. This slowed up the repatriation of art treasures, including archives, libraries and museum objects as well as paintings.

(35) Hermann Beenken, in The Ghent van Eych re-examined, The Burlington Magazine, Vol LXIII (1933) pp. 64-7

The French version of Caring for Old Master Paintings (La Restauration des Chefs Oeuvre) PDF CD has high resolution images. Some photographs, previously in black and white are now in full colour. I have unlocked the file so you can easily down load pages and study them.

Matthew Moss - The man and the artist

An Important and beautifully produced book that makes a valuable addition to the artist's place in the literature of present-day art

Matthew Moss first came to the attention of the art-loving public when he exhibited the Sacred heart No.1 in his native Dublin. It was a gently stated satirical view of a pictorial image that had crept in unquestioned to establish itself as part of the furniture of most Irish households. As a Dubliner, Matthew's art is in a tradition starting from the medieval Book of kells through to the expressionism of Jack B Yeats, brother of the poet William Butler Yeats, in his enjoyment of the drama in handling pigment. The artists and writers of Ireland work under the handicap of a dominating neighbour who, in the past, has not hesitated to claim them as her own once recognition had been achieved. Matthew's art is strong and elegant, balanced in composition and conscious of its cultural origins.

Like many contemporary painters, the artist Matthew Moss displays an interest and a curiosity in the structure of natural forms in the landscape, using them to create a new and valid reality. his major works include landscapes executed in the distant rain-forests of far north tropical Australia where a soft and delicate green, reminiscent of Ireland is superimposed on the antipodean scene. As Matthew says, 'in experiencing the harshness and the dangers of the Australian Bush, the curious light, the uniqueness of the shapes and the forms and the newness of the landscape itself I was presented with a completely new artistic vocabulary to work with.' From the artist's Monte-Carlo studio comes his interest in the sculptural forms of the Rivera's fortified hill villages, red roofed and set off against the blue of the Mediterranean sea. The book traces his early years, when poverty, hostility and indifference gave Matthew a singularness of purpose and a determination to persevere in the creation of a new type of reality in painting. Matthew Moss shares a similar craftsman background to the French artist George Braque whose craftsman painter stimulated in him a love of the materials of the painter's art. The Appendix describes in detail, a number of the paintings, their technical details and the history of how and when they were painted.

An extract from this significant and attractively produced book

Chapter 4

The Australian Paintings

The earliest painting extant from Matthew Moss' arrival in Australia is a landscape of the old Victorian quarter known as Port Melbourne with the sweeping Westgate bridge then under construction. The paintings done in Italy had depicted fortified medieval villages overlooking vantage points above the Mediterranean. The landscape of Australia by contrast was a mostly timber one with the material being extensively used in both domestic and commercial architecture to good effect. This new type of subject matter, in contrast to the massive form of the Italian landscape, imposed a more linear style on his work. In the countryside beyond Melbourne timber architecture was to be seen in abundance. It was used for farms and outbuildings, dividing the paddocks with weather-worn posts and railings and dotted over the landscape as dead trees and grey tree stumps. Also unusual for a European painter coming upon it for the first time was to see all the buildings roofed in corrugated iron, a material associated elsewhere with farm sheds and warehouses. In Australia it was used with much imagination and elaborate architectural permutations in the roofing of rural houses.

As he began painting the Australian landscape he was conscious of seeing for the first time, a completely fresh subject. he began to take these new elements, the rusting warped sheets of corrugated iron roofs, twisted grey timbers of abandoned farm buildings and the many kinds of Eucalyptus trees, and use them as a new vocabulary, seeing what new possibilities could be wrought from them.

While the artist lived and worked in Ballarat, which had sparked the great Australian goldrush in the 1850s he produced the important River at Snake Gully. It was so called because the region in which it had been painted was the home of the vicious tiger snake. It is a painting of deep greens combined with light acid tones and yellows and represented the use of much scumbling, glazing and overpainting. The work owes its deep tones and soft matt appearance appearance to the absorbent and dark brown priming on which it was executed. The Paw Paw Trees is the largest of of three canvases carried out in the tropical rainforests of northeastern Australia. the other two canvases depicting an area of mangrove swamp, were brought to a lesser state of completion because of the physical conditions involved in working out of doors in a jungle area.

The canvas was painted close to the mangrove swamps, in the garden of a house belonging to a prawn fisherman which was on stilts and of corrugated iron. Apart from modifications to the design of the roof and the water tank beneath, the work remains essentially the same as when worked on in-situ. What principally attracted the artist was the abundance and variety of trees there which ranged from the dying palm on the left to the banana plants on the right. They sail into the air and form a baroque frame to the sky, with the dark shadows of the jungle reaching down to the rear of the house and forming a backdrop. The central theme of the painting is the group of three papaya or pawpaw trees set to the left of centre canvas, which sweep to the top of the roof and reveal a fourth beyond. At the base of the trees are scattered fallen ripened coloured fruit . the theme of the papaw trees is repeated in the dark background sketchily indicated in dark green.

Matthew Moss - The man and the artist is an elegantly produced hardbound 240 by 180mm gold embossed book. the monograph contains over sixty pages of text printed onto heavy cartridge paper and accompanied by twenty full-coloured illustrations of the artist's landscapes, tipped in by hand. This is a rare technique which has almost disappeared except in the case of fine-art publications. The book is the product of the best Italian craftsmanship. Its countersunk illustrated binding is protected by a clear acetate cover.

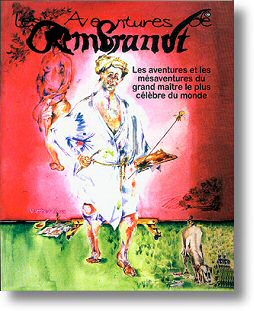

The Adventures of Rembrandt

The adventures and the misadventures of the world's most famous Old Master

Rembrandt's existence is a microcosm of all artists lives. The most modern of the Old Masters, his life and adventures in seventeenth-century Amsterdam are a mirror of the vicissitudes, domestic and economic difficulties with in-laws and social insecurity that afflict all artists.

Rembrandt the Old Master is the superstar of art. The romantic nineteenth-century literary reverence for the artist and for the product of his genius has roots going back to the Renaissance and to writers like Vasari who created the cult of the Old Masters. The icon-like status with which the public regards Rembrandt brings in its wake reactions that are often contradictory. His paintings appear to have magical, spiritual or, even, malignant powers. They have, on more than one occasion, proven a powerful magnet for obsessive and unstable individuals. The Night Watch or, The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq, was attacked in World War I, in 1975 and later, in 1990, dosed with sulphuric acid. Danaë, a large and important early canvas, was largely destroyed in June 1985, by an unbalanced visitor to the Hermitage using acid and a knife.

Rembrandt studies is now a flourishing mid-sized industry. World leader in the monumental undertaking to identify the corpus of genuine Rembrandts extant is the Rembrandt Research Project (RRP) founded in Holland, in 1968. Research in identifying Old Masters as originals is fuelled, partly, by financial and economic interests. Serious money may be at stake on a Rembrandt being genuine, no fobbing off with copies, works by students, followers or, heavens forbid, forgeries. International institutions, market intermediaries and private collectors suffer a loss of prestige and personal reputation when research, radiography, scientific analysis or conservation reveal that a painting formerly attributed to Rembrandt is not, after all, by the Master.

The identification of genuine Rembrandts from his earlier working years has become more accurate in recent years. Thanks to constant scholarly research, historians and specialised scientists now use techniques like dendrochronological dating to measure tree rings on the timber used as supports for paintings. The rings can indicate the date the tree trunk was cut down, ceased adding new rings, and consequently the probable date Rembrandt used the oak panel. Later in life he largely abandoned oak panels and used canvas more and more frequently.

In 1947 the Belgium expert of Flemish art, Professor Paul Coremans, suffered the art equivalent, at the hands of a irate collector, of shooting the messenger. As prosecution witness at Hans Van Meegeren's trial, Coremans demonstrated successfully the techniques that had been used to create Vermeer forgeries. Van Meegeren was on trial as a war profiteer and enemy collaborator. He had profited by selling a number of his do-it-yourself Vermeers to private collectors and, not least, to Fieldmarshal Hermann Göring. The erstwhile Vermeers collector who had, unwittingly, bought several forgeries from Van Meegeren subsequently sued Professor Coremans. He complained that Coremans by his revelations had devalued, irretrievably, his collection.

The void that separates the pecuniary value of a Rembrandt and the works of his colleague and studio collaborators, first-rate artists the likes of Jan Lievens or Willem Drost, Govaert Flinck, and the legendary Carel Fabritius, is immense. The latter's paintings were often attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn. The rights Rembrandt acquired when he took on apprentices makes the identification of genuine works by the master more complicated. The Articles of Indenture privileges he obtained allowed him to sign his students' paintings as being by his own hand. This created much subsequent confusion, the Rembrandt signature on a painting might be genuine although the painting itself was not by the Master. Indentured apprentices were the Seicento (seventeenth-century) equivalent of modern-day artists who, frequently, are obliged to sign Work for Hire contracts that restrict the copyright access to and enjoyment of their own creations.

THE ECONOMIC DIFFICULTIES OF GOING OUT OF STYLE

Seventeenth-century artists, on the other hand, felt freer to investigate new intellectual avenues in perspective, chiaroscuro, and rendering a likeness in portraiture. Painting's artisan aspect became of less importance. In the 1629 Artist in His Studio (Boston Museum of Fine Arts) we see Rembrandt before his grinding slab and muller used to grind and mix his raw pigments with linseed, poppy oil or resin. Even then the artist's apprentice carefully preparing the Master's colours was becoming superfluous. Colours were becoming available ready prepared and mixed and available commercially in convenient-to-use pigs' bladders. The paint-filled bladder and similar contrivances went the way of the grinding stone with the invention, in early Nineteenth century England and France, of the tin paint tube. In addition, Rembrandt and his contemporaries resorted increasingly to buying ready-prepared canvases from specialists. Supply shops, joiners and art merchants provided them with standard-size cut and prepared timber panels. The timber panel as a painting support, and, to a lesser extent, sheets of beaten copper, remained in common use in the Netherlands for some time after they had been replaced by stretched linen canvas elsewhere in Europe.

Holland's Golden Age was fickle in its choice of styles, subject matter and painting techniques. Fashions changed from one decade to the next. Adrian Brouwer, Benjamin Gerritsz. Cuyp, and Rembrandt in his middle years, practiced a bravado manner and favoured earthy motifs. A more elegant style and subject matter gradually replaced it. The tight, highly finished and polished technique of Gerrit Dou, Ferdinand Bol or Govert Flinck that followed the Flemish and Italian schools became sought after. The result was a reduced demand for Rembrandts. Other baroque artists, such as Rembrandt's Italian contemporary Gianlorenzo Bernini, suffered a similar decline in reputation. In later life Bernini's Baroque style could not hold out against the new fashion for the Rococo his French patrons required. In effect, like Michelangelo, and Rembrandt, he outlived his time. A few generations later the French Revolution and the fall of the Ancien Régime killed off the Rococo style, personified by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806). Unable to accommodate himself to the new fashion for Jacques-Louis David's neo-classicism, the elderly Fragonard spent his later years in poverty.

An accident of history confined painters to one of the less important tradesmen's guilds, shared with cloth weavers, physicians and pharmacists. Despite this drawback, painters' association with the well-to-do in the normal course of work meant that, as a class, they were unusually active social climbers. They were conscious, from the early part of the Renaissance onwards, of the need to discard their medieval craftsmen image. It helped that the painter's craft itself had provided him with the very tools useful to upward mobility. He could describe himself in paint in any manner he pleased: As a handsome, young man, dressed in fine clothes and gold jewellery, leaning casually against marble Palladian columns and antiques, a classical landscape visible in the background. In his early years, the prosperous and recently married Rembrandt depicted himself, in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie portrait, in this elegant manner, with Saskia seated on his lap. He was following in the tradition of Rubens, his immediate predecessor, and, long before that, of Albrecht Dürer. This reassuring self-portrait of prosperity and success often conflicted, for the majority of artists, with harsh economic reality.

Velázquez, when painting Pope Innocent X's portrait, and to avoid any misunderstanding felt it necessary to carefully explain that he was, above all, a nobleman who also was skilled in the art of painting. In the delicate diplomatic peace negotiations between Spain and England's Charles I, King Phillip IV took to task the Archduchess Isabella for employing as an ambassador Rubens ‘a mere painter'. Peter Paul Rubens, equipped with a trophy wife, was an active and successful hunter of honours and titles of nobility a fact that was noted, wryly, by some of his contemporaries. He, and many other prominent Northern artists of the day, displayed their success by building very fine residences or, in Giulio Romano's Casa Pippi at Mantua, palaces. Today, the artists' architectural influence on the ambient is less benign. By necessity artists move into economically depressed towns or run-down neighbourhoods in order to obtain cheap living quarters and workshop space they can afford. Art galleries, fashionable stores, boutiques and art camp-followers move in behind the more successful artists. Gentrification and hollowing out raises property prices and rents, drives working-class inhabitants away, and kills off local shops and the services they depend on.

In 1639 Rembrandt, using part of his wife Saskia van Uyenburgh's dowry, bought a small and expensive mansion in Sint-Anthonisbreestraat, now the Rembrandthuis, financed by an interest-bearing loan from the seller, Christoffel Thijs. Rembrandt was not able subsequently to keep up repayments and in 1653 under threats of repossession was forced to take out short-term high-interest bearing loans to pay off the owner. Unable to meet the various notes as his creditors called them in, bailiffs seized his property, including the house, his collection of Old Masters and his own paintings and drawings. In subsequent bankruptcy proceedings the prices realised by the various sales of his property were insufficient to pay off the sums he owed. As a result, Rembrandt remained an undischarged debtor for the rest of his life.

Rembrandt's extravagant lifestyle, resulting money problems and incessant court battles with Saskia's relatives have a quite modern flavour. Rembrandt's domestic situation deteriorated with Saskia's death in 1642. Their marriage contract had established that he could continue to enjoy the use of her estate only if he remained a widower. This state of affairs created friction with Geertje Dircx who, hired to look after his infant, Titus, put pressure on him to marry her. Geertje eventually took him to court in 1649 for breach of promise. Under the settlement terms reached in the action, Rembrandt paid Geertje a life pension; this, coinciding with a slowdown of painting commissions, aggravated his already deteriorating financial circumstances. He managed, none the less, to have her committed to a home for fallen women. This distasteful episode allowed Rembrandt the freedom to turn his attention to a new housekeeper, Hendrickje Stoffels, the subject of many subsequent paintings.

During his years of prosperity, Rembrandt, who was an enthusiastic and regular frequenter of Amsterdam's public auctions, was often prepared to pay high prices for the engravings of well-known artists like Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), a fellow citizen of Leiden. Equally, in order to establish a strong market for his own etchings and to keep prices high, his strategy was carefully to retain possession of his original engraved copper plates and, simultaneously, buy up such of his etchings as came on the market. Rembrandt's attempt to corner the market in Rembrandt etchings, however, necessitated much larger financial resources than he could muster. His lack of success in antiques dealing (in general a profitable sideline for artists) placed him, eventually, at the mercy of his creditors, forcing him, in 1660, to declare himself insolvent. The frequency with which artists, up to the mid-nineteenth century, engaged in dealing in paintings and antiques is surprising. Artists today are largely excluded from this profitable market, lacking as they do the close contact and familiarity with the Old Masters that an earlier generation took for granted. The conscious desire to emulate one's predecessors, to learn from earlier masters by studying and copying their works or reutilising designs of admired earlier painters, is a concept unfamiliar to present-day artists. Rembrandt's paintings show his love of antiques. The are filled with images of shining steel armour, gold breastplates, jewellery and the oriental stuffs and costumes that he possessed. Rembrandt's financial speculations were not an isolated case. The landscape painter Jan van Goyen, who incidentally, dealt also in antiques, suffered disastrous financial losses speculating in the 1636–37 Dutch tulip bubble.

The withdrawal of the Spanish Army under Prince Allesandro Farnese from the Netherlands at the beginning of the 1600s, and the effect of the Calvinist iconoclast riots, destroyed, at a stroke, an important source of income for seventeenth-century Northern artists, that of the nobility and the church. Artists' loss of earnings was compensated only partly by the emergence of a Flemish mercantile middle class. Dutch middle class taste tended to portraits, genre and landscapes of the wall-furniture school of painting. The economic conditions under which artists tried to earn a living were often desperate and surprisingly similar to the laissez faire climate they work under today. Genius being no respecter of class, talent was likely to strike equally the poor as much as the well-off artist; Adriaan Brouwer as much as Rubens, George Morland as Sir Joshua Reynolds. Then, as now, it was, with rare exceptions, the well-capitalised intermediary or the wealthy collector that profited from the artist's talent. In 1950, Georges Rouault, then an old man, complained bitterly how Ambroise Vollard the dealer had enriched himself, at the artist's expense at a time when Rouault was unknown and little appreciated by the public at large.

In 1940s working-class Dublin, Rembrandt's 1630 self-portrait etching depicting him as a beggar would, had it been known, have struck a familiar chord. Parents of children, suspected of displaying artistic tendencies, would threaten them with a similar unpleasant future. The illustration most often used was the elderly bearded pavement artist who, for many years, practiced his trade beneath the classical colonnades of Gandon's ancient Irish House of Parliament, now the bank of Ireland. Incessant rain showers make painting outdoors in Ireland, whatever the medium, a discouraging experience. However, the artist had chosen his work-site astutely; it was protected and, being in the centre of the city much trafficked by pedestrians. This genial location guaranteed him a steady income if an exiguous existence. If Pliny the Elder's poor opinion of artists is to be relied on, and despite the romantic aura painters acquired through the eyes of nineteenth-century writers, the life of the artist has been often short and brutal: up until the 1960s many now-prominent Irish artists were auxiliary art instructors at the National College of Art and forced at the end of each term to sign on to the dole in order to try and survive until the following academic year. Anthony Flinck, the father of Govert, who worked as a journeyman painter with Rembrandt in 1635, regarded his son's trade as morally suspect, in all likelihood condemning him to a life of loose women and strong drink. One can understand why many artists of Rembrandt's era took the easy way out and married into money. Jan Steen, on the other hand, obtained a license in 1672 to run a tavern in his hometown of Leiden and managed it until his death in 1679. It was a clear sign of the superior profits to be derived from a licensed premises compared with an uncertain income from art.

AFFLICTIONS THAT BEFALL ARTISTS' CREATIONS

Society often treats the paintings of even the greatest artists from the past with remarkable indifference. Often, Rembrandt's masterpieces have reached us vandalized, reduced in size, strips of the original painted canvas cut away from the sides, top and bottom and, often, all four sides together. The classic example is The Night Watch. When the painting was relocated, in 1775, from its home in the Amsterdam militia's meeting place to the Town Hall, large pieces of the original painting were trimmed from the left-hand side and the bottom of the canvas in order to make it fit into the reduced dimensions of its new location. Later generations of painters have suffered similar indignities. During the London National Gallery's transfer of its irreplaceable artistic treasures for safekeeping to the slate mines of Wales in anticipation of World War II, staff uncovered fifty of Turner's paintings, previously mistaken for rolls of ancient linoleum, in the Gallery's basement. They lay there ignored and overlooked, from the time of his death in 1851. The thief who, in the 1990s broke into David Hockney's British residence displayed by his actions how most people see and value artists and their creations. With a realistic grasp of art market economics most painters only dream of, he stole electronic household objects that, obviously, had a secure if modest cash value disregarding completely the original Hockneys hanging on the walls.

THE ARTIST'S TECHNIQUE

Matthew Moss' youthful connection with Rembrandt, his life and works, began with a travelling scholarship in the history of art (the Purser Griffith) that Dublin's Trinity College awarded him for a thesis on Rembrandt's etchings. He next graduated from the Istituto Centrale del Restauro in Rome, (famous for saving some of the greatest masterpieces of Italian art). In Dublin he established the first art conservation laboratory in what is considered one of the twelve most important European art museums, the National Gallery of Ireland. Then followed fifteen years when he happily restored and cared for this unique collection of Old Masters. It presented the artist with an unparalleled opportunity to acquire, at first hand, a deep understanding and knowledge of the museum's Rembrandt and School of Rembrandt paintings. Rembrandt's signed and dated masterpiece The Rest on the Flight into Egypt was one of the many Netherlands paintings that Moss eventually restored. The National Gallery collection contains not only Playing ‘La Main Chaude,' an early painting by the artist, but also masterpieces by Rembrandt's followers and students. They include Pieter Lastman his early master, Gerbrandt van den Eekhout, Ferdinand Bol and Govaert Flink. (It was Govaert Flink's more customer-orientated style that made inroads, with such disastrous effects, into Rembrandt's client base during his middle years). Matthew Moss' closeness to Rembrandt during those years at the National Gallery created a love and a deep knowledge of the Dutch Master, his often difficult life and the times he lived through.

The materials the artist used to paint The Adventures of Rembrandt series are quite similar to those used by Rembrandt and other Netherlands artists of the period. The choice of these particular tools is not an attempt to, as the Pre-Raphaelite and Nazarene painters did with the art of the Quattrocento, to recreate retro watercolours in the style of Rembrandt.

Artists have used these materials, watercolours included, from antiquity onwards. A perspicacious observer will note that some of the watercolours have been created using bamboo and reed pens. Costa Rainera, a beautiful medieval Italian Riviera mountain village overlooking the Mediterranean, provided the artist with reeds from the surrounding streams and rivers. Matthew cut away the tips from the seasoned reeds to provide oblique pointed pen nibs. Two of the pigments Rembrandt himself used to apply washes to his drawings are bistre, an antique blackish-brown pigment, and sepia, the beautiful rich brown pigment derived from the ink sacs of squid, While bistre is not easy to obtain today, sepia itself is freely available as an ink and is used in watercolours. They give the delicate wash tones that are a distinguishing feature of some of The Adventures of Rembrandt.

Bibliography

Alpers, Svetlana, Rembrandt's enterprise: the studio and the market, Chicago 1988

Beck, Hans-Ulrich, Jan van Goyen 1596–1656 Exhibition, Richard Green Gallery catalogue 1996

Bevers, Holm: Schatborn, Peter: Welzel, Barbara, Rembrandt: the master and his workshop drawings and etchings, New Haven and London 1991

Farr, Dennis: Bradford, William, The Northern Landscape, London 1986

Haak, Bob, Rembrandt drawings, London 1985

Il Museo Jacquemart-André, Beaux Arts Magazine, 1996

Johnston, Edward, Writing & Illuminating & Lettering, London 1956

Keaveney et al., National Gallery of Ireland, London 1990

Liberman, Alexander, The Artist in his Studio, New York 1960

Lindsay, Jack, Turner, the man and his art, London 1985

Monaco Mon Amour, Rembrandt references pps. 13, 28, 40, Monaco 2005

Moss, Matthew, Caring for Old Master Paintings pps 46, 103 etc., Montreal 2003

Moss, Matthew, Restored Paintings, catalogue of paintings, restored in the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin 2nd ed. 1971

Pliny the Elder, Chapters on the History of Art, translated by K. Jex-Blake, commentary by E. Sellers, London 1896

Rembrandt et son école : dessins du Musée du Louvre, Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, catalogue Paris 1988

Schama, Simon, Rembrandt's Eyes, New York, 1999

Sleiter, Rossella, Tra Santità e Maestà, Il Venerdi, 11 Marzo 2003

Monaco Mon Amour

The Renaissance in the Principality of Monaco.

Old Master paintings in Monaco, yesterday and today.

The Principality of Monaco has a long tradition going back to the Renaissance of encouraging artists to work and live in Monaco. The important early Renaissance painter Louis Bréa, and to a lesser extent, his brother Antoine, were already seriously engaged in executing important commissions through 1500 and 1505 in the Principality .

THE OLDEST OLD MASTER PAINTING OF NOTE in the Principality of Monaco is the Saint Nicolas altarpiece, painted around 1550 by Louis Bréa and today in the Cathedral of Monaco. This masterpiece displays the styles of the contemporary Avignon and Catalonia with some traces of Flemish art. There is also a notable references to the schools of southern Germany.

It is, however, the style of Liguria and Piedmont that dominate Monegasque art in the following centuries. The geographical influence of Louis Bréa extended from Savona - where he collaborated in 1490 on important paintings with Vincenzo Foppa (a master of the post-Gothic style) to Genoa and Palazzo Bianco. Louis Grimaldi - a nobleman then the owner Palazzo Bianco - may have commissioned the altarpiece and other important works from Bréa. The altarpiece of Nicolas Saint - one of the rare extant works of art from before the French revolution which were not destroyed or dispersed - is the starting point of Monegasque art that continue to the present day. Stefano Grimaldi tutor of the future heir to the throne of Monaco, Onorato ler - converted the architectural style of the castle of Monaco from its original form of a heavily fortified medieval structure and also its interior, closer to that of the palaces of contemporary Genoa nobility.

The close links which existed between Genoa and Monaco were the reason why the painters of Genoa - and in particular the frescos painters working for the for the Dukes of Grimaldi in Genoa - were called in to decorate the Prince's recently rebuilt palace. Lazzaro Calvi was one of the first contracted artists. Born in 1502, - he died at a hundred and five years age, his style reflecting those of Luca Cambiaso and Pierin del Vaga. Del Vaga was one of Raphael's students and was commissioned fresco the palaces of Andrea Doria and the other notable of Genoa. One of the consequences was that he imprinted his style - and indirectly that of Raphael - on Ligurian and Monegasque paintings in the following centuries. The particular style of frescos painted by Del Vaga in Monaco - called grisaille - is still practised in present day Liguria.. The flowers and the Grotesques animals that Pierin del Vaga painted above the arcades and in the medallions of the main courtyard of the Princely Palace of Monaco show the influence of Raphael.

They were a new interpretation, inspired by the Renaissance, of the ancient Roman art and bas-relief sculpture of its architectural style. The classical Roman manner reappear not only in Raphael's paintings, but also in Mantegna and, of course, Michelangelo. The frescos on the Main courtyard of the Princely Palace of Monaco's façade,The Labours of Hercules, have also been attributed to Luca Cambiaso of Genoa(1527 - 1585) frequently employed by the Grimaldi family to work on their palace in Genoa. he may have collaborated around 1552 with Lazzaro Calvi. In the following centuries the frescos degraded seriously, though it is recorded that, in 1870, they were still visible when an attempt to preserve them was made by the artist Philibert Florence.

Current conservation research technologies now available will possibly one day allow us to see and appreciate the grandeur and beauty of these lost masterpieces of Monegasque art so long hidden and, to a certain extent, considered as lost to posterity.

Another Genoa painter of the Baroque school, Bernardo Strozzi (1581-1644), inherited the style of Luca Cambiaso. His painting combines the styles of Lombardy and Tuscany which for a long period characterized the Ligurian School. Bernardo Strozzi's long sojourn in Venice left the imprint of Titian and Tintoretto's intense colours. The Ligurian painter ended his days on the Venetian lagoons that had so profoundly influenced his manner of painting. One of Strozzi's more beautiful canvases, Summer and Autumn is today in the National Gallery of Ireland.

Monaco Mon Amour has a preface, introduction, short if interesting, bibliography and an index.

Annuaire de Artistes de Monaco

FINE ARTS IN THE PRINCIPALITY OF MONACO

Monaco's Montmartre

THE PORT OF MONACO has become the new Mediterranean Montmartre. Once the Principality's factory district, the port of quai Antoine l enjoys a renaissance as the cultural and recreation district of the Principality.

The introduction to the Annuaire describes the rehabilitation of a once industrial zone in the Nineties as new spaces for the development of an art centre, with areas for the presentation of contemporary art. The impetus was provided by the Belgian artist, Jean-Michel Folon. He recorded the contribution made to twentieth century Paris by another waterside quartier, the Bateau-Lavoir in Montmartre,.creative home to Picasso, Juan Gris, Modigliani and others. The project may also have been inspired by a similar undertaking in 1960s New York's down town SoHo where industrial buildings were rehabilitated and renovated to the needs of artists.

The Monaco installation has nine artists studios, a public exhibition space of almost one thousand square meters reserved for art events, an art gallery and accommodation for Monegasque cultural organizations. Some of the nine workshops, were set-aside for, amongst others, Valerio Adami, Arman and Fernando Botero international artists with ties to the Principality and the Nice region of France.

The first section of the Annuaire describes, with illustrations, these contemporary painters. The volume is divided into, painters and sculptors, musicians, writers, media artists, the theatre and cultural associations. Each artist's page contains a biography, full contact details and an update of their artistic activities, useful for researchers wanting to keep informed on the cultural activities of the Principality. It is a particularly helpful source of information that is not otherwise easily available. A necessary tool allowing you to communicate with this important category of Monegasque society. Contains an interesting historical biography section (homages) and index.